As you may have noticed, I am a bit behind and off schedule in documenting the scintillating chronicles of my attempts to submerge my awareness of the present in inexpensive wine. However, I could ask the question: Need one who is unemployed keep a strict schedule? To which I could answer: No, one needn’t. One could instead lie around all day and listen to the Polish producer/composer Jacaszek’s delightful neo-classical melding of electronic and chamber orchestra music.

And so it has come to this, dear readers:

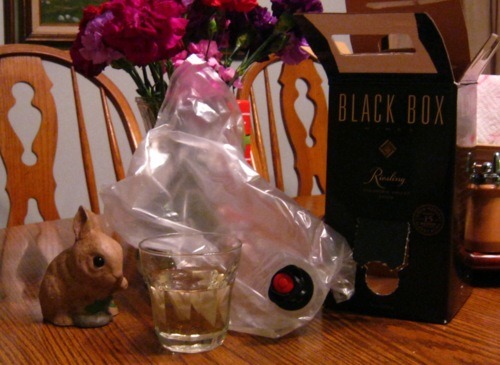

Not a morsel of food in sight; only a gutted cardboard shell of Black Box Riesling whose innards have been extracted rudely and drained ruthlessly of their numbing nectar. This is a vintage I have enjoyed before, despite the fact that it also is not, as I explained on a previous Wednesday eve. But we can discuss the unique manner in which my Riesling came into being on this night a bit later. For now, allow me to gather my thoughts as I (re) experience this familiar, yet novel wine.

As I sit, struggling to savor what may be my last glass of sweet white wine in the foreseeable future, I cannot help but draw a parallel between my current situation and that of a figure painted by the brilliant French artist Édouard Manet (1832-1883), a precursor and familiar of the Impressionists.

|

| Édouard Manet, the Absinthe Drinker, 1859; oil on canvas; Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. I encourage you to click the highlighted text to visit the website of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, where you can view Manet's canvas in great detail. The bravura brushwork employed here by the artist, and by another addressed later, will play a significant role in the discussion below.

Like me, this vagabond is down to his last few gulps, which is indicated clearly by the overturned bottle in the foreground. Nevertheless, Manet sought to ennoble this urchin by equipping him with a top hat, a sartorial signifier of haut bourgeois status, at least, as can be seen in Gustave Caillebotte’s famous depiction of upper-class pedestrians strolling Parisian boulevards.

|

|

| Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street; Rainy Day, 1877; oil on canvas; Art Institute of Chicago. |

Manet bestows a further degree of dignity to his hobo by the figure’s cocksure stance – the toe of his casually extended left foot rests daintily on the ground – and the implacably calm expression, which signals thoughtful detachment. Additionally, the man’s drink of choice, absinthe, was popular at the time with artists, intellectuals, and bohemians generally for its hallucinogenic properties, which may or may not lend weight to the impression that this tramp may be capable of insight that the uniformed denizens of Caillebotte’s painted milieu are not.

Manet’s work is a distinctly modern take on an established genre, akin to this week’s music selection. The philosophical ambience of the Frenchman's scene was inspired by paintings of the great Spanish Baroque master, Diego Velázquez (1599-1660). Manet had viewed the Spaniard’s works during a trip to Madrid and likely encountered the following canvas, and others like it, while promenading through the Prado.

|

| Diego Velázquez, Aesop, 1640; oil on canvas; Madrid, Museo del Prado.

Here we see Velázquez’s rendering of Aesop, the ancient Greek fabulist, in the guise of a seventeenth century peasant. His vestments consist simply of a formless measure of burlap cinched at the waist by a swath of linen. His knotted, irregular physiognomy finds a visual parallel in the lumpy pile of rags in the bottom right corner of the painting. The only indications of the figure’s identity as an intellectual – apart from the inscription at the top right of the canvas – are the manuscript gripped in his right hand and, like Manet’s figure, the unwavering expression and piercing gaze, here directed steadfastly at us, conveying quiet confidence and suggesting some unique insight, though this time hallucinogens are apparently not required.

|

In conceiving of this painting, Velázquez himself was undoubtedly relying on a literary and artistic trope that extends back to antiquity: That of the destitute, malnourished man of intellect who disregards physical and material cares in favor of philosophical pursuits. Famous examples (apart from myself) include Socrates, who in Plato’s dialogues often mentions his poverty and lack of concern for the conventions of Athenian society, and the fourth century Cynic philosopher Diogenes of Sinope, who also lived in Athens in Plato’s time (and who thought Plato to be a ponce). Diogenes characterized himself as “Socrates gone mad” due to his militant asceticism, which included living in the streets in an empty tub. So hostile was Diogenes to established customs and corporeal cares that he instructed his followers to toss his corpse to stray dogs upon his death, because it was of no importance. I am positive that this sentiment was the inspiration for a particularly poignant statement made by Frank Reynolds, Danny Devito’s character in the television show It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, which testifies to the continued relevance of Diogenes’ demonstrative philosophical teachings.

The wonderfully maniacal, demented comic stylings of Mr. Devito call to mind the work of a third artist participating in the tradition of depicting ragged philosophers, Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652). Ribera was a Spaniard as well, though one who spent nearly all of his artistically active years in Naples, Italy, which was under Spanish control at the time. I have selected his remarkable rendition of Archimedes, the ancient Greek mathematician, for our discussion.

|

| Jusepe de Ribera, Archimedes, 1630; oil on canvas; Madrid, Museo del Prado. Again, I urge you to view the linked image, which is of magnificently high quality, though I will include details a bit further on. |

Ribera’s brushwork also contrasts starkly to that of Velázquez and Manet, emphasizing the impression of antisocial psychological pathologies conveyed by his painting, as I will attempt to demonstrate momentarily. But first, let’s return to Manet’s work and examine it in detail. Manet was greatly inspired by Velázquez’s loose, seemingly casual handling of paint, in which broad, unblended, apparently rapidly applied strokes coalesce into a coherent image.

|

| Manet, The Absinthe Drinker (detail). |

Here, in this detail of the lower left leg and foot of Manet’s figure, you can see the straightforward simplicity of the artist’s approach. Rather than conscientiously modeling – depicting the three-dimensionality of an object by showing the gradual gradation from areas highlighted by light to those in shadow – Manet employs summarily broad strokes of just two or three different tones, as well as a gratuitous application of black, to cursorily signify the roundness of the leg. Even more exemplary of Manet’s manner of handling pigment is the shadow cast by the partially uplifted foot, which is constituted simply by a single leftward pull of the brush. The rough textures of the ground and the stone ledge on which the figure sits are indicated in a similar fashion: Each consists of a field of one color – tan for the ground and an olive hue for the ledge – into which darker shades, and black itself, were applied quickly and haphazardly while the original layer was still wet. This type of brushwork – at once seemingly careless, but also casually assured – reinforces the relaxed, confident bearing of the figure depicted.

On the other hand, we have the fastidious facture of Ribera:

|

| Ribera, Archimedes (detail). |

In this wonderfully high-resolution image, we can see that, instead of an expansive, brisk, flowing application of a limited number of hues and shades, Ribera carefully enunciates each tone – from pure white highlights to the deepest shadows – and applies these varied tints of the figure’s flesh color in careful, finicky touches. Each application of paint can hardly be called a stroke, but seems to have been calculated painstakingly in regard to the amount of paint deposited, as well as its length, width, and direction.

That last consideration – attention to the direction of the brush's movement – is, in my opinion, one of the keys to Ribera’s brilliance. If you glance once more at a detail of Manet’s canvas, you will find broad swaths of paint, the direction of which matters little. Manet does not define form by the movement of his brush (at least in this work, which is one he executed early in his career), but rather by juxtaposing relatively large, ill-defined areas of different colors and shades. Contrastingly, close examination of Ribera’s painting reveals brushstrokes moving in every imaginable direction, almost as if a three-dimensional form existed already and the Spaniard was methodically pushing and pulling paint over, along, and into its bumps, curves, and crevices. This meticulous attention to detail can also be seen in a close-up of the hand of Ribera’s mathematician:

|

| Ribera, Archimedes (detail). |

Note that the artist has here altered his strokes – again, as opposed to Manet, who used fairly consistent coups throughout his painting – in order to articulate the different texture of the hand's skin compared to the face's, as well as the shape of the appendage itself. Most telling is the manner in which Ribera pulls the white over the knuckles, sculpting in two dimensions the knotted bone structure. Also remarkable is the stroke of white highlighting the nail of the index finger, the intensity of which is greater than the other whites in its immediate vicinity by only an infinitesimal degree. This miniscule divergence serves effectively to differentiate the smooth, hard, more reflective surface of the nail from the leathery, weathered skin around it.

In a fantastic contradiction, Ribera employs mind-boggling meticulousness to create images that are coarse, unrefined (at least in terms of his paintings’ frequent inhabitants), and often violent. (Check out the link for a particularly gut-wrenching painting, which is one of my favorites. Also, those of you living in DC should be sure to visit the Ribera in the NGA.) Though my meandering ruminations began with Manet and his confidently cavalier style, my habits and approach to life are closer to the anxious scrupulousness suggested by the exacting touches of Ribera’s brush. A further parallel between the adopted Neapolitan and myself is that, for all my solicitousness and circumspection, the final product is likewise a figure in utter disarray, in shambles: Hence my recourse to the bottled or boxed yields of the vine, when I can afford it.

In one final conjunction of careful rigor and reckless raggedness, I attacked the sack of wine pictured at the outset with a steak knife, inflicting a small, but far from surgically precise, puncture wound from which I withdrew the last few precious drops. By flowing over the serrated blade the wine gained a metallic flavor, which added a distinct note of frenzied desperation that I do not remember tasting upon my initial experience of this vintage. Though slightly unpleasant, I know little else: Thus, while I may greedily gulp this piercingly accented drink to lubricate my austere journey toward either philosophy or madness, I cannot in good conscience recommend it to others.

(Published originally on January 19th, 2012.)

No comments:

Post a Comment